So what is grit? In a 2013 report called Promoting Grit, Tenacity, and Perseverance: Critical Factors for Success in the 21st Century, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology defines grit as, “Perseverance to accomplish long-term or higher-order goals in the face of challenges and setbacks, engaging the student’s psychological resources, such as their academic mindsets, effortful control, and strategies and tactics.” Let’s unpack that definition to get a better idea of what grit looks like in the classroom.

|

Growing up in the country, I often heard, “When you fall off a horse, get right back on again!” Although my family did not have horses, only chickens and cows, I appreciated the message about refusing to give in to minor setbacks. Whether it is called grit, perseverance, or tenacity, the refusal to give up when faced with a challenge is a key component of success, both in the classroom and in the real world.

So what is grit? In a 2013 report called Promoting Grit, Tenacity, and Perseverance: Critical Factors for Success in the 21st Century, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology defines grit as, “Perseverance to accomplish long-term or higher-order goals in the face of challenges and setbacks, engaging the student’s psychological resources, such as their academic mindsets, effortful control, and strategies and tactics.” Let’s unpack that definition to get a better idea of what grit looks like in the classroom.

0 Comments

Many educators ponder this question: “How do I get my students to want to learn?” Some students do not necessarily want to come to school every day and be challenged to achieve high standards. Traditionally, motivation has been applied with a simple input-output model. Teachers praise students for their hard work and support their motivation to persevere through difficult situations. This cause-and-effect model could very well work in many instances; however, educators and researchers alike need to understand that student motivation is more complex than that. Cause-and-effect may be easily replicated within a laboratory, but not necessarily in a classroom. Why? Because students come to schools with a host of social contexts, including religious backgrounds, family dynamics, race, socio-economic status, and other factors, which all affect motivation.

As a first-year teacher, I thought entry tasks had one primary purpose: to keep the students quiet and occupied long enough for me to take attendance. During my first two years of teaching, I tended to assign a lot of simple, skills-based activities as entry tasks. I was an English teacher, so my students typically had grammar or vocabulary exercises during the first five minutes of class. However, as I observed other teachers through my STAR training and grew stronger in my own instructional practices, I began to look for ways to raise the level of thinking and application in my lessons. As my lessons began to demand more from my students, so too, did my entry tasks. Although I still started one or two lessons a week with skills-based practice (there is always a place for that!), I began to focus more on activities that asked my students to think critically and to make connections from the moment the bell rang. Here were three of my favorite entry tasks.

We read about it all the time – students of lower socioeconomic status (SES) do not perform as well academically as those from higher SES. SES refers to the mix of economic, educational, and social factors that encompass the differences in economic wealth (such as educational opportunity and attainment), social status, and the ability to control aspects of one’s life. Both laboratory and societal research point to early enriched environments as essential to success. They also show that stress, which is often found in households of low SES, can adversely affect cognitive function. Given the wealth of information on the cycle of reduced opportunities for enriched experiences and stress effects on cognitive development, a seemingly basic question would be, “Can we change this cycle? And, if so, how?”

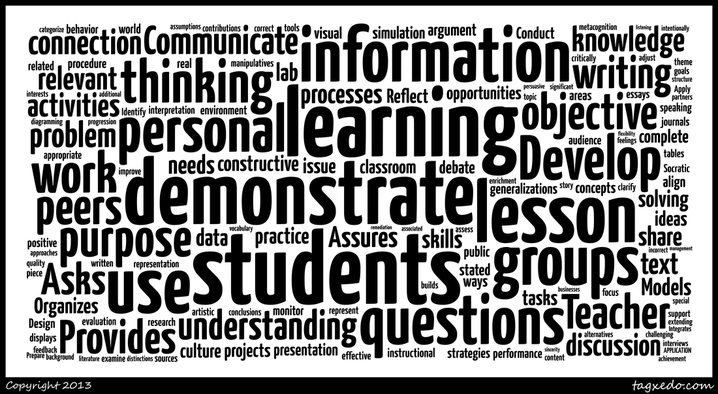

To get a different perspective on the STAR Framework (v2012), we decided to take a look at it in the form of word cloud. In this cloud, the bigger the word is in the cloud, the more times it showed up in the content of the framework. An a fun exercise, we loosely strung words of similar size, starting with the largest, to see if they would communicate anything useful. We thought the results were pretty interesting. Take a look: students demonstrate learning Do you see any interesting connections? Interested in learning more about the STAR Framework?

Student achievement is higher when the Essential Components of Powerful Teaching and Learning are evident in classroom practices. These components include Skills, Knowledge, Thinking, Application, and Relationships. In observations I have conducted, Application has usually been the lowest scoring component. This means that students are often not given the opportunity to make relevant and meaningful personal connections to their learning. Teachers can quite easily provide opportunities for students to make these connections by incorporating student culture into the classroom.

|

The BERC Blog

SubscribeSign up to get our posts in your inbox.

Recent Articles

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|